Thought of the Week

As I mentioned last week, Congress is currently on its month-long August recess; coincidentally, yesterday marked the 200th day of Donald Trump’s presidency. Rather than focusing on putting out daily policy-related fires, Congressional recesses typically allow government affairs types time to sit back and contemplate some of the grander questions we often get—like, why doesn’t Washington move faster…as if passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act wasn’t fast enough…or whether it’s a Democrat or Republican in the White House, are we moving toward a more executive-centered Republic? Politico touched upon a similar theme in its podcast this week when it considered that the most salient dividing line in party politics right now isn’t left vs. right vs. center, nor progressive vs. conservative, nor even centrist versus populist, but it is the divide between institutionalists and disruptors; their conclusion: at the moment, those who want to bring a shock to the political system are on the march. The Constitution’s place in any of these discussions boils down to a defined separation of powers and system of checks and balances, which divides U.S. governmental authority among three distinct branches—the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. The concept of a separation of powers, although refined by Enlightenment thinkers like Locke and Montesquieu, has its roots in ancient political thought. While Aristotle identified three distinct functions of government: the deliberative (legislative), the magisterial (executive), and the judicial, he didn’t advocate for these functions to be exercised by separate, independent branches. Checks and balances existed to some degree in Rome, with public assemblies, the senate, and public officials all operating with varying degrees of independence. The U.S.’s Founding Fathers took Ancient Greece, the Roman Republic, and the Enlightment all into account, by incorporating not just a separation of powers in the Constitution, creating three distinct branches—the legislative (Congress), the executive (President), and the judicial (Supreme Court), but also fashioning a system of checks and balances, where each branch has the ability to limit the power of the other two, further preventing any single branch from becoming overly dominant. Currently, two cases are making their way through the pipeline that will put both the separation of powers and system of checks and balances to the test. The first involves the EPA’s intent to roll back its 2009 “endangerment finding,” which constitutes the basis for regulating greenhouse gases, has underpinned regulation over the past 16 years, and is the foundation of government efforts to address climate change. The second challenges President Trump’s use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to impose tariffs on most U.S. trading partners. That either of these two issues are being considered is due to last year’s Supreme Court ruling overturning the Chevron deference doctrine, a long-standing principle that directed courts to defer to federal agencies’ interpretations of ambiguous laws written by Congress. Up until last June, the bureaucracy’s expertise was relied on to resolve complex and subtle questions not specifically addressed by Congress in the legislation. A final decision to uphold the endangerment finding and/or the IEEPA tariffs has the potential to fundamentally reorder the separation of powers between Congress and the executive branch. In fact, analysts tell us that there is a greater than 50% chance President Trump will prevail on the endangerment question, but also a better than 50% chance he will lose on the tariff issue. When will we know? It will be months, or even years, before the Supreme Court makes its final rulings. Which gets us back to the question, why do things take so long in Washington? Answer: it was designed to be that way.

Thought Leadership from our Consultants, Think Tanks, and Trade Associations

Capital Alpha says, “Wow, that Came as a Surprise.” Last week, the Trump administration went forward with previously announced plans to repeal the Obama administration’s 2009 Endangerment Finding, which is the bedrock legal determination on which U.S. climate regulation rests. Analysts had not previously given the Trump administration high odds of success, but they have since changed their minds. The White House’s proposal turns on major decisions from the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Roberts, and particularly on Loper Bright v Raimondo in 2024. There is now a good chance the Roberts Court will uphold President Trump’s repeal of the Endangerment Finding, which asserts that economy-wide regulation of greenhouse gases is a major question that should be left to Congress. The result may be a more stable regulatory outlook for power plant construction, including new gas-fired power plants to support data centers.

Capstone Speaks to the Trump Administration. Capstone analysts met with senior Trump administration officials, who delivered a remarkably consistent message: they plan to streamline energy permitting for fossil fuels through a variety of mechanisms, including the use of artificial intelligence to manage environmental reviews, expanding exclusions under the National Environmental Policy Act, and offering white-glove service to coordinate permitting across federal agencies. DOE will leverage its emergency authority to retain aging fossil fuel infrastructure, as well as seek additional levers, in coordination with FERC, to enable the development and interconnection of new dispatchable resources, such as natural gas, nuclear, and geothermal, to support resource adequacy and data center development. Capstone believes FERC, once Trump nominees are confirmed, will focus on (1) prioritizing thermal and fossil resources in wholesale power markets; and (2) promoting and expediting the permitting of natural gas infrastructure. Additionally, FERC will favor utilities—ultimately de-risking the outlook for transmission-related incentives and return on equity. The Department of the Interior will use numerous policy levers to support expanded energy production on federal lands, including the ability to increase the size, quality, and frequency of oil, gas, and geothermal lease sales; lowering oil and gas royalty rates; and providing producers with operational flexibility. Also, DOE’s Loan Programs Office is well-positioned to support the development of new nuclear, geothermal, critical minerals, and transmission and pipeline projects while deprioritizing funding for renewables; hydrogen; and carbon capture, utilization, and sequestration (CCUS) projects, among other non-baseload technologies.

Eurasia Group Believes that Despite the August 1st Increases, the Effective U.S. Tariff Rate Will Land Between 13-17% by Year-End. President Trump’s announcement of new tariffs pushed the average effective tariff rate up from 16% to just below 18%. Despite this increase, it is likely that year-end tariff rates will land in the 13-17% range (60% odds). The decision to exempt roughly 40% of Brazilian exports and ongoing negotiations around product exemptions with the EU set the stage for other nations to receive similar treatment.In fact, exemptions are the key to lowering the effective rate on major trade partners. The EU will be looking to conclude discussions on exemptions for products such as generic pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and agriculture that were announced by EC President von der Leyen. In addition, likely deals with India, Taiwan, and Canada will remove some of the largest increases. Consider that tariffs on India appear particularly designed to push talks over the finish line rather than impose durable restrictions on trade. The decision to impose a 39% tariff on Switzerland was a surprise as was the threatened action against drugmakers that don’t reduce U.S. drug prices. It is expected that pharma rates will land at roughly 15% for major exporters, with implementation in late August or early September, though this hinges on the Swiss rate being negotiated down. The Trump administration also signaled that a decision would be made in coming weeks on “rules of origin” to determine which imports will face an additional transshipment tariff.

Observatory Group Asks Whether President Trump is Undoing the Cold War He Started with China During Trump 1.0. President Trump has executed a marked shift in his China policy—transitioning from a hawkish “reverse Nixon” strategy in his first term to a more traditional “Nixon-style” détente in his second. The pivot is partially driven by China exerting control over the rare earth supply chain, and the White House’s subsequent desire to secure a grand economic bargain with Xi Jinping, driven not by ideology nor strategic alignment, but by transactional instincts and a desire to showcase personal diplomacy. In his first term, President Trump stood apart from the U.S. establishment by pushing aggressive tariffs and tech restrictions on China. Even as Washington has grown more hawkish, today, he is retreating from that position—making him the new outlier in the more hostile consensus he helped create. China’s rare earth export restrictions hit the U.S. economy hard and served as a major inflection point. This pain helped motivate the recent softening of restrictions, including the reversal of the export ban on Nvidia’s H20 chips and the scrubbing of Taiwanese President Lai’s U.S. transit stop. These recent actions, and others, signal that Taiwan and tech controls are now negotiable in Trump’s calculus. While still muted, GOP unease is emerging, although overt opposition remains limited due to Trump’s dominance over the party. The “three T’s” for a grand bargain include: (1) Tariffs: reduction to a 15–35% range, including removal of “fentanyl tariffs” in exchange for nominal Chinese cooperation; (2) Tech: a freeze or cap on U.S. export controls; and (3) Taiwan: to include reining in President Lai, U.S. rhetorical concessions, arms sale slowdowns, and diplomatic sidelining. At present, President Trump seems willing to entertain many of these to announce a symbolic breakthrough with Xi; a Trump–Xi Summit should be expected around late October. The White House wants a high-visibility ceremony where optics matter more than bureaucratic progress. The recent denial of President Lai’s U.S. stopover and the scrubbing of defense dialogues signal a strategic U.S. downshift to avoid provoking Beijing before any summit. The structural divide—ideological, military, and geopolitical—between the U.S. and China makes any truce fragile, and Beijing’s persistent assertiveness in the Taiwan Strait and South China Sea will continue to undermine trust. The Trump administration’s openness to negotiating Taiwan’s status and easing tech restrictions could provoke a bipartisan backlash in Congress, especially if China overreaches its demands. If President Trump gives China a better economic deal than allies like Japan or South Korea, alliance cohesion in East Asia will suffer. At the same time, Beijing may overplay its hand, misjudging how far Trump can bend without provoking political costs.

“Inside Baseball”

Most K Street leaders expect Congress to pass China competition legislation before the end of the year, according to a Punchbowl News survey of top lobbyists. Countering China isone of the few areas of strong bipartisan agreement in Congress. Lawmakers are primarily concerned about intellectual property theft, cyber espionage, and China’s advancements in AI and biotechnology. Among the respondents, 47%of Democrats and 58%ofRepublicans said Congress will pass competition legislation aimed at China.A plurality of lobbyists, 42%, said it’s likely the administration will reach a trade deal with China by the end of the year (Treasury Secretary Bessent is leading trade negotiations with China and said last week that the two sides had “the makings of a deal”). Since May, there’s been a 90-day break on escalating tariffs on Chinese goods; that pause expires August 12. More Republicanlobbyists (53%) than Democrats(31%) said it’s likely a trade deal happens. Members of the Washington office participated in the survey.

In Other Words

“I asked him just last night, ‘Is this something you want?’ He does not want it—he likes being Treasury secretary,” President Trump affirming that Treasury Secretary Bessent is not in the running to be the next Federal Reserve chair. The president said he had four people in mind, including NEC director Hassett, former Fed governor Warsh, and two unnamed individuals, which may include current Fed governors Bowman and Waller, both of whom dissented from the decision to hold rates steady at the July meeting.

Did You Know

While Dwight D. Eisenhower was the first American president to have a pilot’s license, it was Theodore Roosevelt who was the first president to fly in an airplane. He took a short flight in a Wright biplane on October 11, 1910, after leaving office.

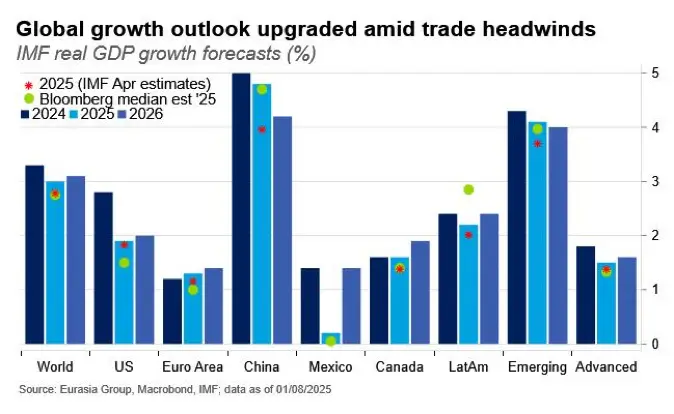

Graph of the Week

IMF Lifts Growth Forecast as Economies Withstand Trade Headwinds. In its July World Economic Outlook (WEO), the IMF increased its global growth forecast for 2025 to 3.0% and for 2026 to 3.1%. Broadly, the April-to-July adjustments reflect lower average effective U.S. tariff rates, stronger-than-expected front-loading in anticipation of higher tariffs that supported activities in Europe and Asia, and an improvement in global financial conditions given falling inflation and dollar depreciation. The U.S. growth estimates were raised by 0.1% for 2025, and 0.3% for 2026. Front-loading, lower tariffs, a weaker dollar, and fiscal expansion (with some offset from weaker immigration and a faster-than-expected cooling in private demand) all helped boost the U.S. economy. Chinese growth was also revised higher by 0.8% to 4.8% for 2025, and by 0.2% to 4.2% in 2026. This reflects both a reduction in U.S. tariffs and stronger-than-expected activity in the first half of the year. As in April’s WEO, risks remain to the downside: unpredictable U.S. trade policy, geopolitical risk, potential tariff-induced inflation in the U.S., and elevated public debt. Bottom line: the U.S. policy mix remains stagflationary, and the global outlook remains subpar, significantly below the 3.7% pre-pandemic growth rate and 0.2% below pre-Trump forecasts.